Underwater Forest

Date: May 10, 2019 Author: Allie Carroll

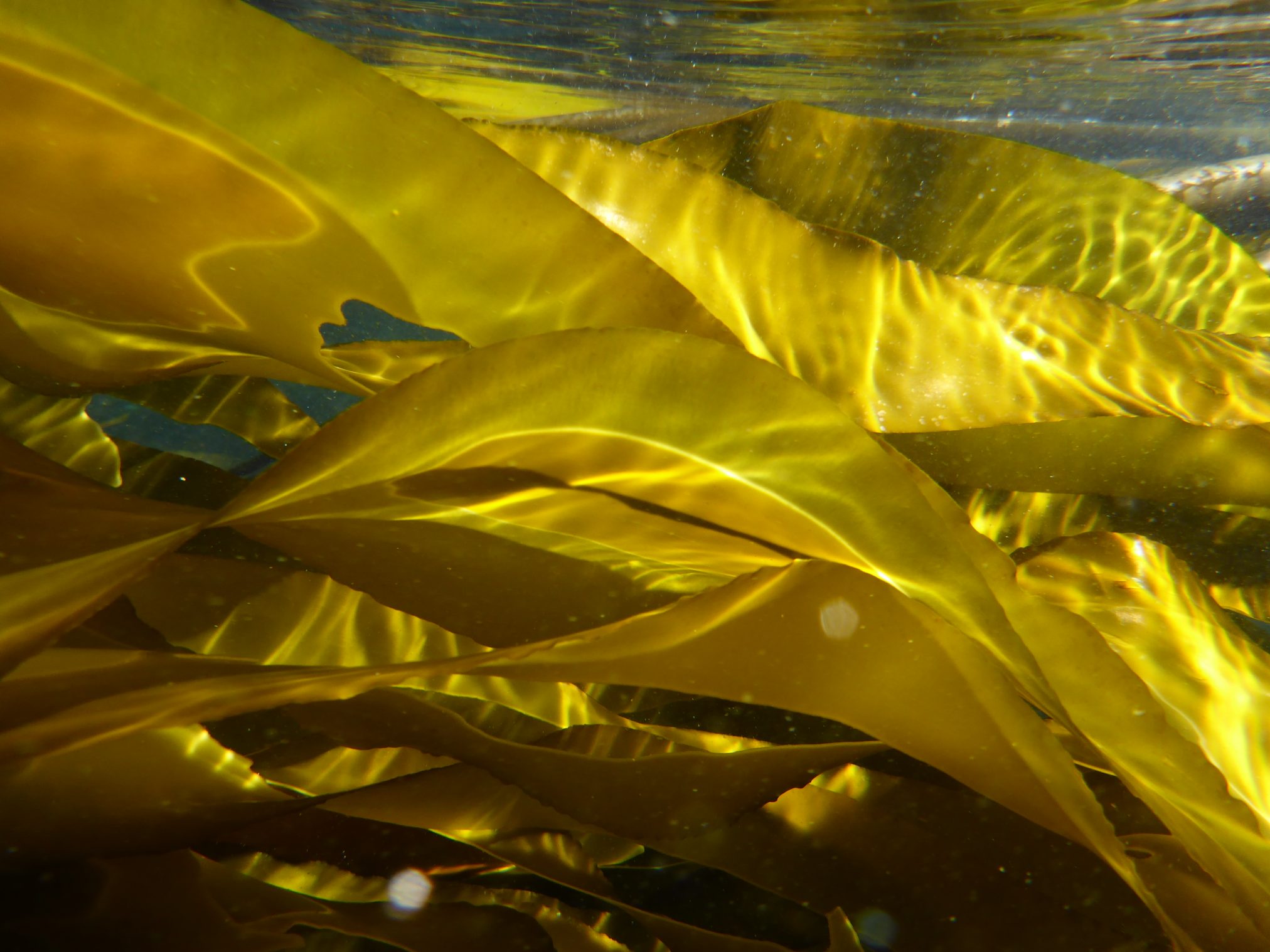

Kelp Forests

Paddling in the Pacific Northwest is an opportunity to surround yourself with all kinds of marine life. While this area also offers up world class diving, there is more than enough to see at the surface, or, from the vantage of sea level – in a kayak. With waters so clear, you certainly don’t need a mask and snorkel either. Time your paddle at low tide, stick close to the rocky shores, and there you’ll find a veritable aquarium at your paddle- tips! However, one of the more under-appreciated species to see is seaweed, or macroalgae.

Seaweed can be found, in actuality, in a broad zone – from several meters below low tide, to high up where it’s only wetted by the fine sea spray. It can be attached to the rocky shoreline, in tidepools, or extended several miles out to sea. Most commonly, seaweed has a firm attachment point to the ocean floor or the aforementioned rocky shorelines. Here on the west coast there’s an old saying “when the tide is out, the table is set!” and seaweeds are an abundant inclusion in this buffet. Traditionally, First Nations on the coast would line steam pits with the blades, generating steam and flavouring food; when fishing, wrapping kelp blades around the freshly caught fish would keep it fresh in the canoe; the hollow tubes of the kelp stem would be filled with eulachon oil using a second bulb as a funnel to fill the first stem, and a carved wooden plug tied in place would seal it for travel and trade. You can pickle it, eat it raw, smoke it, dry it…just use your creativity!

When taking groups paddling in my home waters, there are often two reactions to expansive floating beds of bull kelp: obliviously paddling right over top of it, or complete evasion of these floating green slimy things. Rarely until I stop to introduce the bull kelp, does anyone voice a curiosity of it. But maybe in their efforts to concentrate on their paddling form, they’re unable to see the kelp forest for the trees, or, blades as it were. They seem to miss the fact that there is a real underwater forest right below them, and while we may grasp the significance of our terrestrial forests – do we take note of it’s marine equivalent?

Much like it’s terrestrial equivalent, kelp forests provide homes and shelter to many animals such as snails, crabs, fish, shrimp, sea stars, jellies and anemones. Certainly, if smaller critters are residing here, larger predators will be found here as well. Seals, seabirds and herons will all hunt for food in the kelp forest. In fact, the Great Blue Heron adapts to life in these deep ocean waters by using the kelp beds as their ‘shallow water’ wading grounds, standing atop the kelp beds to hunt. Even humpback whales have been known to enjoy a pleasurable rub among the floating fronds of the kelp blades.

Also similar to terrestrial forests, kelp forests are complex ecosystems and can be divided into different layers: the canopy layer, the blades or fronds of the kelp; the understory, much like the shrubs and bushes on land; and the forest floor, with many more creatures living among the substrate here. The density of the canopy layer effects what and how much can grow underneath it, by how much light is let through. Not surprisingly, kelp forests provide oxygen to our planet – at least 70% of the oxygen we breathe is supplied by marine algae, both in fresh and saltwater. They photosynthesize carbon dioxide into oxygen, and life on earth simply couldn’t survive without it!

So the next time you are out paddling on the ocean, take a moment of pause in the kelp beds, look below the surface of the water to see what you can see, and share a little gratitude for these marine forests!

– Allie Carroll

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.